My wife isn’t that into motorcycles. She doesn’t mind going for a ride every now and again, and I’ve even gotten her to go on a few weekend trips. It’s OK, because it gives us something to talk about that I’m excited about and she can nod and mutter “Yes, that’s nice,” and we both feel like there’s been a conversation.

At breakfast one morning in October, she said, “We should go for a ride. Maybe even go away for the weekend in the sidecar.” My mind filled with options, plans, routes and ideas. We talked about it for 15 minutes before she had to leave for work, and I resolved to move my rig out from under the tree where it slumbered all summer, go put some fresh gas in it, and get it ready for a weekend jaunt.

Imagine my surprise and dismay when, at the stop sign at the end of my street, I discovered my front brakes were completely non-functional. Gone. One hundred percent useless. Luckily, I live in a rural neighborhood, so nobody cared (or hit me) when I blew past the stop sign while relying solely on the rear brake to halt my forward progress.

Disappointment was the word of the day, but we’re both glad I discovered the defect before hitting the highway. When I got safely back to my driveway, I scolded myself for not doing TCLOCKS or SCMODS or whatever it’s called when you give your bike the once-over before riding off. You can go ahead and scold me for it, too, but I have a bad habit–as I suspect many of you do as well—of just getting on the bike, starting the engine and riding off. Lesson learned.

Back in the driveway, in the harsh light of day and without the covers on the rig, I could clearly see the telltale signs of leaked brake fluid on the right side panel. Not just a few drops, either, but a lot of it. Just to be sure, I took the cover off the master cylinder and sure enough, there wasn’t any brake fluid left in there at all. I pumped the lever a few times and…nothing. Dollar signs flashed before my eyes as I wondered what a new master cylinder would cost (p/n 32 72 7 650 773, $536.89), and I shed a single tear at the prospect of all that brake fluid ruining my beautiful paint.

First things first, though. A call to the number on the back of my MOA Membership Card triggered my Roadside Assistance plan, and I remain grateful for the 100-mile towing aspect of the MOA’s Roadside Assistance program. After the 87-mile tow to the shop—which, by the way, we have renamed from Beemers Uber Alles to Gridlock Motors for a variety of reasons—my boss, George Mangicaro, seemed nonplussed. “Yeah, this happens,” he said. “How long was the bike sitting?”

Shamefully, “I don’t know” was all I could answer.

“When’s the last time you flushed the brake fluid?” was his follow-up question.

I couldn’t even make eye contact with him at that point. It’s that old adage about seeing doctors smoking at a hospital: we always tend to take better care of our clients, customers or patients than we do of ourselves. I would never let a customer leave the shop without reminding them to “have that brake fluid flushed in a year!” but apparently, I don’t follow my own advice. Looking back through my maintenance log, I discovered the last time the brake fluid got flushed my 1998 K 1200 RS was in April 2015, when George modified the bike so I could use the handlebars from a K 1200 GT to get a little more steering leverage for the heavy rig. I didn’t need to look at a calendar to know I’d blown past even BMW’s recommended brake fluid service interval of two years by a year and a half.

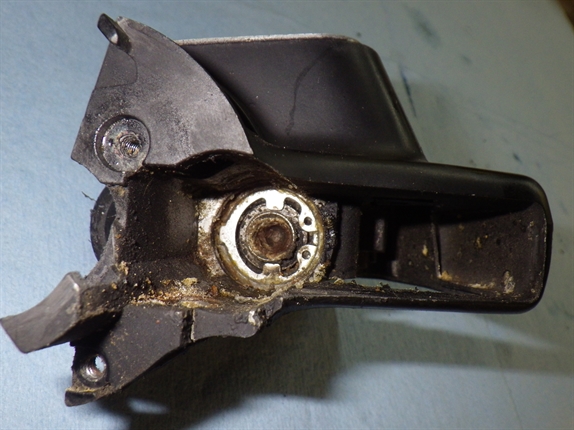

It was no surprise to discover that the reason my brake fluid leaked out was because the rubber rotted out of my master cylinder. My apologies for the wretched photo, but even in a blurry photo you can see the damage done internally by the old, crusty brake fluid.

Lucky for me, we’d taken in a number of parts bikes in the last year before moving the shop, so we happened to have a clean used master cylinder in a bin. (Luckier for me, George organized everything from the old shop before he moved, so he knew exactly which bin to look in to find it!) In just a couple of hours, my rig had functional front brakes again, and I’ve learned an important lesson all over again.

You see, this isn’t my first battle with motorcycle neglect. You may remember a column not long ago in which I encouraged all of you to avoid using cheap parts. I was specifically referring to the KTM shop that put low-pressure fuel lines on my fuel-injected 2007 990 Adventure, something that ended with me stranded on the side of the road due to a burst fuel line. The reason the shop put those low-pressure fuel lines on in the first place was because that bike had been seriously neglected; its previous owner, a friend of mine who unfortunately passed away not long after we made the deal, left that poor KTM outside in Iowa under a cover for about two and half years. When I got the bike home, I quickly discovered a dozen or more things needing attention to deal with rot, cracking, rust and more.

That lesson didn’t even sink in fully, which is why my poor K 12 RS sidecar rig suffered such an ignominious fate. Fortunately, you can learn from my mistake and make it one of your New Year’s Resolutions not to neglect your motorcycle(s). You can achieve that goal (and make a habit of it) by using some of these pointers.

- Flush your brake fluid once a year, front and rear, and include the ABS unit if your bike is so equipped. Be sure to check what type of fluid (DOT 3 or 4 are most common for BMW motorcycles) your bike needs and have plenty of it on hand. Discard unused brake fluid after a couple months of sitting, even in a tightly sealed container; brake fluid is hygroscopic (it absorbs water from the atmosphere), which is why it breaks down over time.

- If your clutch uses brake fluid, flush that once a year as well. If it uses mineral oil (check your owner’s manual to be sure), that doesn’t need flushed as often, as it shouldn’t absorb water from the atmosphere like brake fluid does. Still, it’s not a bad idea to flush it every other year to keep your slave cylinder functioning smoothly.

- Check all exposed rubber—hoses, covers, tires, etc.—for obvious cracks. Heat cycles (cold-hot-cold) and UV exposure degrade rubber over time. Tires with cracked sidewalls should be replaced, and any hoses with cracks should likewise be replaced as soon as possible.

- If your motorcycle is water cooled, flush that system once every two years at the least. Contaminated coolant can quickly become corrosive, which could damage a lot of important stuff on your motorcycle. It’s not a bad idea when the system is empty to pull the water pump and inspect it closely. On some older K bikes especially, the water pump is a known weak point and often needs rebuilding following an inconvenient failure, usually when you’re hours and hours from the nearest dealership.

My resolution is to flush these systems once a year on all my motorcycles, regardless of how many miles I’m putting on the bike. I’m going to extend this resolution to the other oils on the bike—engine, transmission and final drive. At least once a year, no matter the mileage. One of the reasons I let the maintenance go on my sidecar rig is simply because I don’t ride it often. Hopefully that will change in 2019, so please don’t laugh too hard if you see a beautiful blue K 1200 RS with a sidecar with one ugly, stained side panel.